Port Chicago – The Mutiny Trial

In the worst Home Front disaster of World War II, an explosion at the Naval Magazine in Port Chicago, California on July 17, 1944 killed 320 men, of whom 202 were black. The tragedy was followed by a work stoppage and a controversial mutiny trial. This sent ripples of change through the segregated armed forces.

These events are included in my novel Blue Skies Tomorrow.

This is the fourth in a five-part series on the Port Chicago Disaster:

Part 1: Introduction: Segregation in the armed forces and the situation at Port Chicago

Part 2: The explosion

Part 3: The work stoppage

Part 4: The mutiny trial

Part 5: The aftermath and desegregation of the US Navy

Mutiny Trial

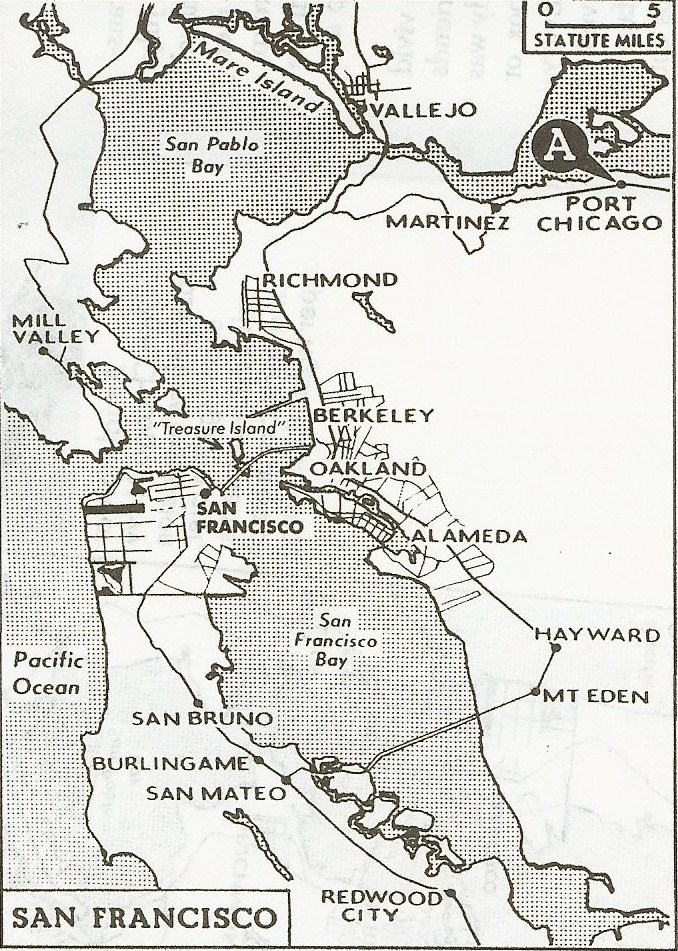

On August 9, 1944, 258 survivors of the explosion refused to load ammunition at Mare Island Naval Depot in Vallejo, California. After the threat of a charge of mutiny on August 11, fifty of these men still refused to load ammunition and were charged with mutiny.

A General Court Martial was convened by Adm. Carleton Wright, commander of the 12th Naval District, with a seven-member court led by Rear Adm. Hugo Osterhaus to act as judge and jury. The prosecution was led by Lt. Cdr. James Coakley. The defense team was led by Lt. Gerald Veltmann and consisted of five additional lawyers who each handled the cases of ten defendants.

The trial was held in a Marine barracks on Yerba Buena Island (also known as Treasure Island) in San Francisco Bay.

Prosecution

On September 14, 1944 the trial opened. Coakley argued that a strike was mutinous in time of war. He dismissed the defendants’ claims, stating, “What kind of discipline, what kind of morale would we have if men in the United States Navy could refuse to obey an order and then get off on the grounds of fear?”

The questioning of the defendants was loaded with racial language, and the prosecutors often disparaged the men’s honesty, especially when their spoken statements contradicted their earlier statements—although the men had complained from the beginning that the transcriptions were inaccurate. One defendant had refused to load ammunition because he’d broken his wrist the day before the work stoppage and was wearing a cast. Coakley replied that “there were plenty of things a one-armed man could do on the ammunition dock.”

Trial for the “Port Chicago 50” at Yerba Buena Island, CA, September-October, 1944 (US Navy photo)

Defense

Veltmann quoted the official legal definition of mutiny: “a concerted effort to usurp, subvert, or override authority,” and argued that the men had never tried to seize command and therefore, were not guilty of mutiny. Since direct orders had not been given to each man, they could not be guilty of disobeying orders. The defense chronicled the discriminatory conditions at Port Chicago, the psychological effects of the explosion and cleaning up body parts, and the unchanged conditions they faced at Mare Island.

Damage at mess hall at US Naval Magazine, Port Chicago from 17 July 1944 explosion (US Naval History and Heritage Command)

Publicity

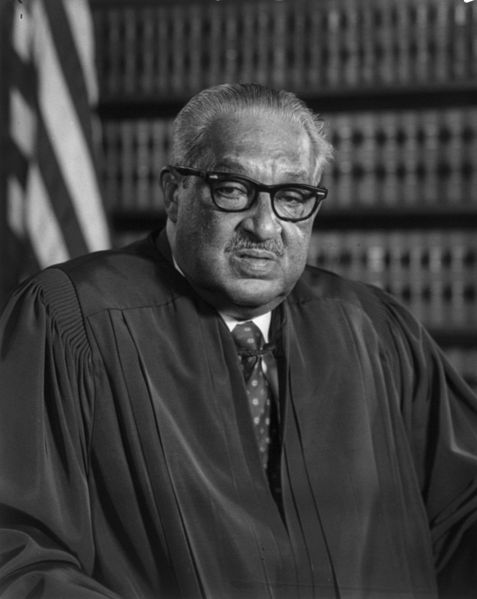

The Navy encouraged the press to cover the trial, and the NAACP sent their chief counsel, Thurgood Marshall (the future Supreme Court justice), who sat through twelve days of the trial. On October 10, Marshall held a press conference and stated that the prosecution acted in a prejudicial manner. On October 17, he issued a statement deriding the conditions in the Navy and specifically at Port Chicago. He believed the men were guilty of the lesser charge of insubordination and did not meet the legal definition of mutiny.

Verdict

On October 24, 1944, after deliberating for 80 minutes, the court convicted all 50 defendants of mutiny, including the man with the broken wrist and two others who had never loaded ammunition previously for medical reasons. All 50 men received 15-year sentences, and at the end of November they were imprisoned at Terminal Island Disciplinary Barracks in San Pedro, California.

Further Legal Action

On November 15, Admiral Wright reviewed the court’s findings and adjusted the sentences to 8-15 years. On April 3, 1945, Thurgood Marshall filed an appeals brief to the Judge Advocate General’s office in Washington, DC. Concerned about hearsay evidence, the Secretary of the Navy asked the court to reconvene. They did so on June 12, 1945, but upheld the sentences. After the war was over, the sentences were reduced. In September 1945, one year was lopped off each man’s sentence, and in October the sentences were reduced to two years for all the men with good conduct and three for those with bad conduct. In January 1946, the Navy released all but three of the men—one remained for bad conduct and two in the hospital. The men stayed in the Navy and eventually received honorable discharges, but the felony convictions remained on their records.

Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, 1976

Continue Reading: Part 5: The aftermath and desegregation of the US Navy

Sources:

Allen, Robert L. The Port Chicago Mutiny. Berkeley CA: Heyday Books, 2006.

The Articles of War. Washington DC: United States War Department, approved 8 September 1920, accessed 25 June 2019.

Department of the Navy. Articles for the Governance of the United States Navy, 1930. Washington DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1932. On Naval History and Heritage Command website, updated 22 August 2017. Accessed 25 June 2019.

Marshall, Thurgood. “Statement on the Trial of Negro Sailors at Yerba Buena, September 24, 1944.” On Organization of American Historians website, printed 20 November 2007.

[…] today I’ll cover the explosion, and over the next few weeks we’ll look at the work stoppage, trial, and […]

[…] I’ll discuss the situation in the armed forces and at Port Chicago, the explosion, work stoppage, trial, and […]

[…] explosion, today I’ll cover the work stoppage, and over the next couple of weeks we’ll look at the trial, and the […]

[…] the situation in the armed forces and at Port Chicago, the explosion, the work stoppage, and the mutiny trial. Today’s post looks at the change that […]