Make It Do – Meat and Cheese Rationing in World War II

Rationing of meat and cheese was an important part of life on the US Home Front. A complex and constantly changing system kept grocery shoppers on their toes.

Why meat and cheese?

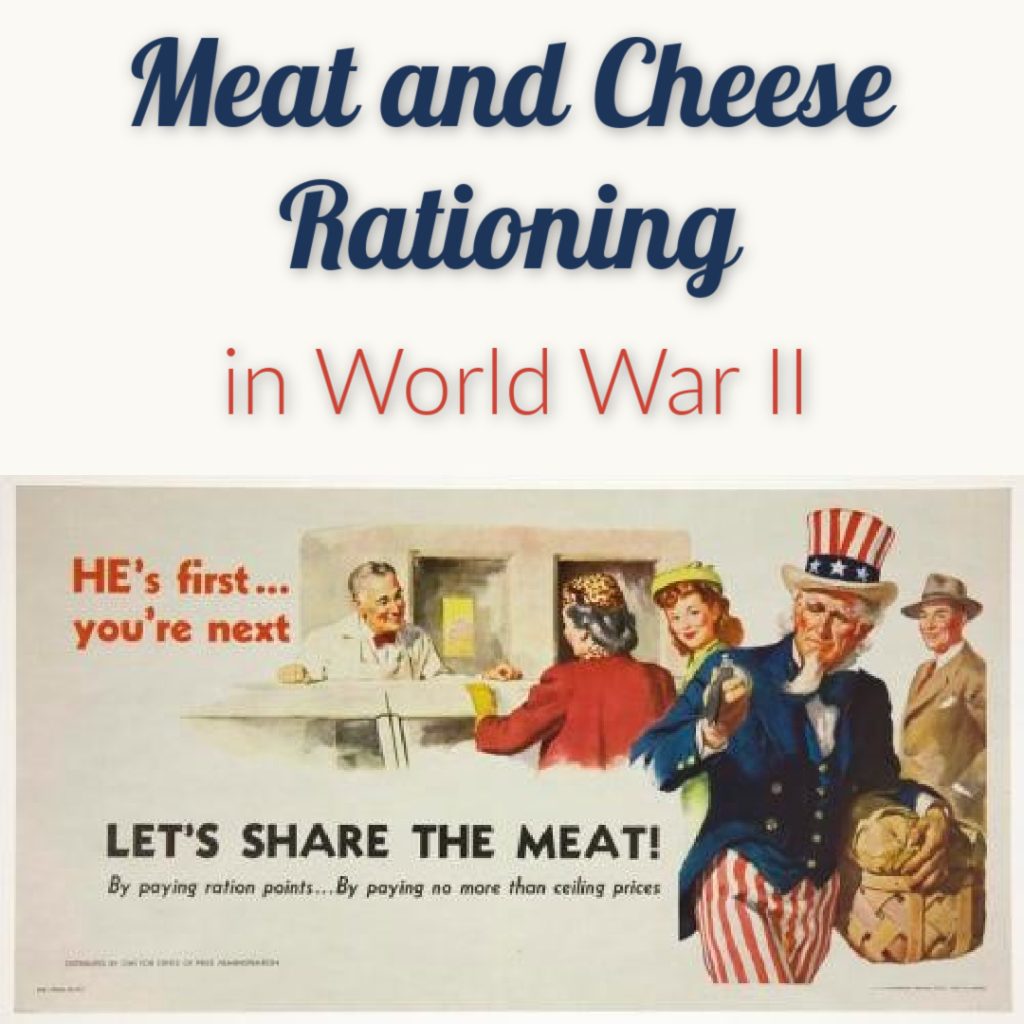

The United States produced meat and cheese for her civilians and military, and also for her Allies. During World War I, food shortages were a serious problem, with hoarding, escalating prices, and rushes on stores. When World War II started, the government reduced deliveries to stores and restaurants, instituted price controls, and urged people to voluntarily reduce consumption. Britain had already instituted a point-based rationing system and had found it effective, so the United States decided to implement a similar program in 1943. Rationing made sure everyone got a fair share.

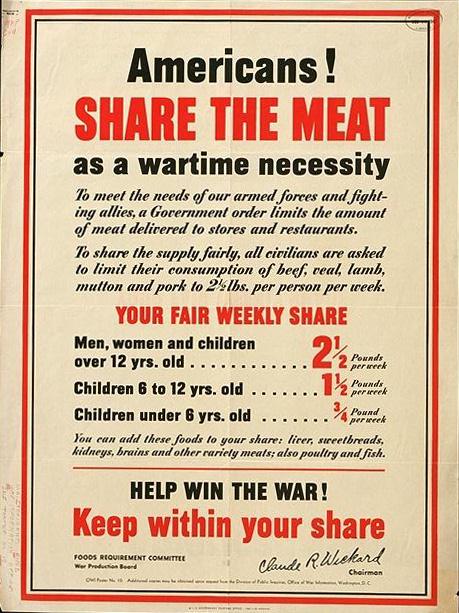

US poster, World War II

What was rationed?

On March 29, 1943, meats and cheeses were added to rationing. Rationed meats included beef, pork, veal, lamb, and tinned meats and fish. Poultry, eggs, fresh milk—and Spam—were not rationed. Cheese rationing started with hard cheeses, since they were more easily shipped overseas. However, on June 2, 1943, rationing was expanded to cream and cottage cheeses, and to canned evaporated and condensed milk.

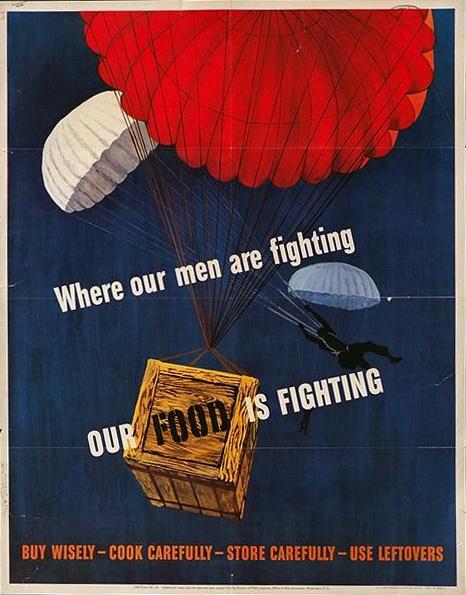

US poster about food rationing, 1943 (US Office of Price Administration)

Ration Books

War Ration Books Two, Three, and Four contained blue stamps for processed foods and red stamps for meat, cheese, and fats. Each person received 64 red stamps each month, providing 28 ounces of meat and 4 ounces of cheese per week. The stamps were printed with a number for point value and a letter to specify the rationing period—such as C8. Rationing calendars in newspapers declared which stamps were current and for how long. To prevent fraud, the stamps had to be torn off in the presence of the grocer. Stamps were good for one, two, five, or eight points, with no “change” given, so the shopper had to be careful to use the exact number of stamps. The system was simplified on February 27, 1944, when plastic tokens were issued as change.

US rationing books owned by my mother and grandmother, WWII (Photo: Sarah Sundin)

Points

Each cut of meat was assigned a point value per pound, based not on price or quality, but on scarcity. These point values varied throughout the war depending on supply and demand. “Variety meats” such as kidney, liver, brain, and tongue had little use for the military, so their point values were low. On May 3, 1944, thanks to a good supply, all meats except steak and choice cuts of beef were removed from rationing—temporarily.

Meat ad from Safeway in the Antioch Ledger (Antioch, CA), 1943, showing points and price

Shortages

After D-day in June 1944, newly liberated countries required food their war-ravaged lands couldn’t produce. The United States stepped forward to meet those needs, but shortages resulted on the Home Front. For Thanksgiving in 1944, the supply of turkeys was short, and on December 31, 1944, all meats were returned to rationing. Even with tightened rationing, a serious meat shortage developed in the spring and summer of 1945. San Diego reported a 55 percent decrease in the meat supply, and in San Francisco, only lamb and sausage were available. For the first time, even chicken and eggs were in short supply. Things improved after the victory parades, and on November 23, 1945 meat and cheese rationing came to an end.

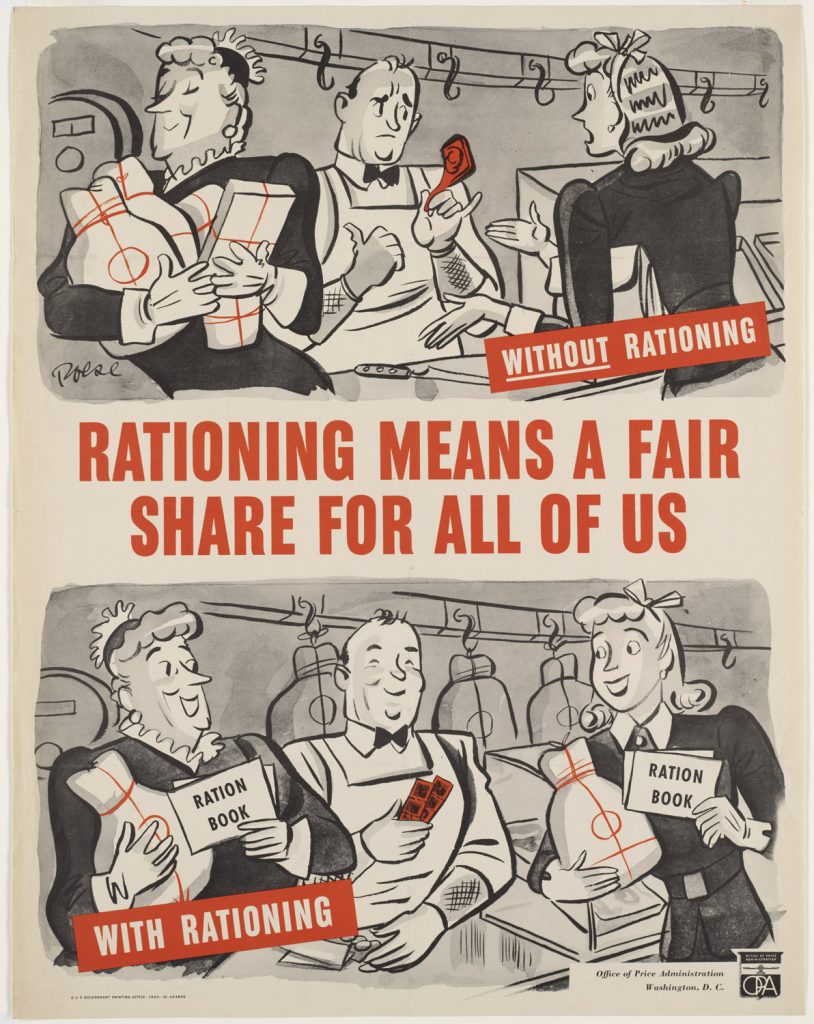

US poster about meat rationing, WWII

Making Do

Throughout the war, American housewives learned to make do with less meat. Chicken and rabbit hutches sprang up in backyards, and people were encouraged to fish. Patriotic citizens observed “meatless Tuesdays” and cut meatless recipes out of newspapers and magazines. Soups, stews, and casseroles helped stretch the meat ration, and housewives learned to adapt recipes to organ meats and poultry.

US poster about meat rationing, WWII