Port Chicago – Desegregation of the US Navy

In the worst Home Front disaster of World War II, an explosion at the Naval Magazine in Port Chicago, California on July 17, 1944 killed 320 men, of whom 202 were black. The tragedy was followed by a work stoppage and a controversial mutiny trial. This sent ripples of change through the segregated armed forces.

These events are included in my third novel, Blue Skies Tomorrow. This is the last in a five-part series on the Port Chicago Disaster:

Part 1: Introduction: Segregation in the armed forces and the situation at Port Chicago

Part 2: The explosion

Part 3: The work stoppage

Part 4: The mutiny trial

Part 5: The aftermath and desegregation of the US Navy

Public Outrage

The explosion and mutiny trial were heavily publicized, at the Navy’s request. While the purpose was to discourage further insubordination in the ranks, the publicity backfired, exposing the segregated and discriminatory practices in the Navy. A great outcry went up in the black community, but many whites were appalled as well.

Further Discord

The difficult and humiliating conditions for blacks in the armed forces caused more strife and violence. On July 31, 1944, 75 black members of the 1320th Army Engineers refused to work on an airfield on Oahu. They were arrested and convicted of mutiny on February 1, 1945. Christmas Eve and Day on Guam were marked by an ugly race riot that killed one black and one white Marine. Forty-three blacks were court-martialed and sentenced; no whites were arrested. And in March 1945, one thousand black Seabees at Port Hueneme, California engaged in a two-day hunger strike to protest discrimination.

Proponents of Change

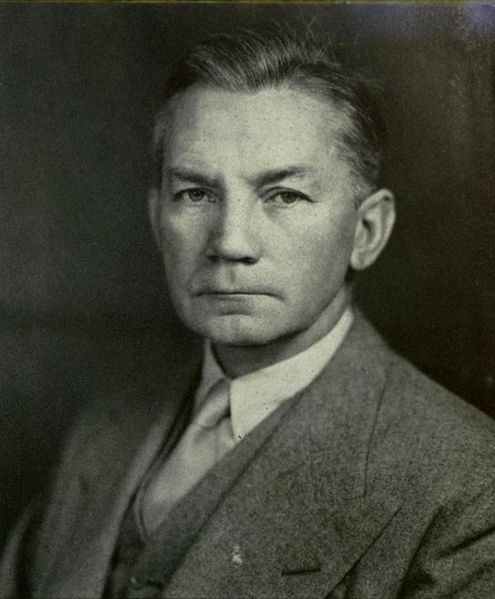

James V. Forrestal, US Secretary of the Navy (US Navy photo)

The black sailor had a friend in the new Secretary of the Navy, James V. Forrestal, who had been appointed by the president on May 19, 1944 after the death of Frank Knox. Forrestal found that Admiral Ernest King, Chief of Naval Operations and Commander-in-Chief of the United States Fleet, believed that integration was right and necessary. In March 1945, Forrestal asked Lester Granger of the National Urban League to serve as his adviser. Forrestal liked Granger’s tactics. Rather than arguing for desegregation solely in the name of fairness and rights, Granger argued that desegregation increased security, production, and administrative efficiency.

Gradual Changes

Ironically, on August 9, 1944, the same day the survivors of the Port Chicago Explosion refused to load ammunition, Forrestal informed the commanders of 25 fleet auxiliary ships that they would be assigned black sailors, to be fully integrated on their crews. In this experimental change, the black sailors were found to be accepted and efficient members of the crews. As a result, all auxiliary ships were fully integrated as of March 6, 1945.

Crew of destroyer escort USS Mason, the first US warship with a predominately black enlisted crew; Boston Navy Yard, 30 March 1944 (US Naval History and Heritage Command)

In January 1945, a pamphlet went out to naval officers, encouraging ratings and promotions be made for blacks on the same basis as for whites. The pamphlet also warned against the use of racial epithets.

In response to the Port Chicago incident, on February 21, 1945, the Navy limited blacks working at ammunition depots to no more than 30 percent of the work force. An argument that proved effective was that dispersing blacks prevented collective action like riots and strikes.

Specialist training schools had quietly been integrating since 1943, simply due to the inefficiency of maintaining separate schools. In June 1945, all Navy training camps were desegregated, with recruits sent to the nearest facility regardless of race. In July 1945, the Navy opened submarine and aviation pilot training to blacks as well.

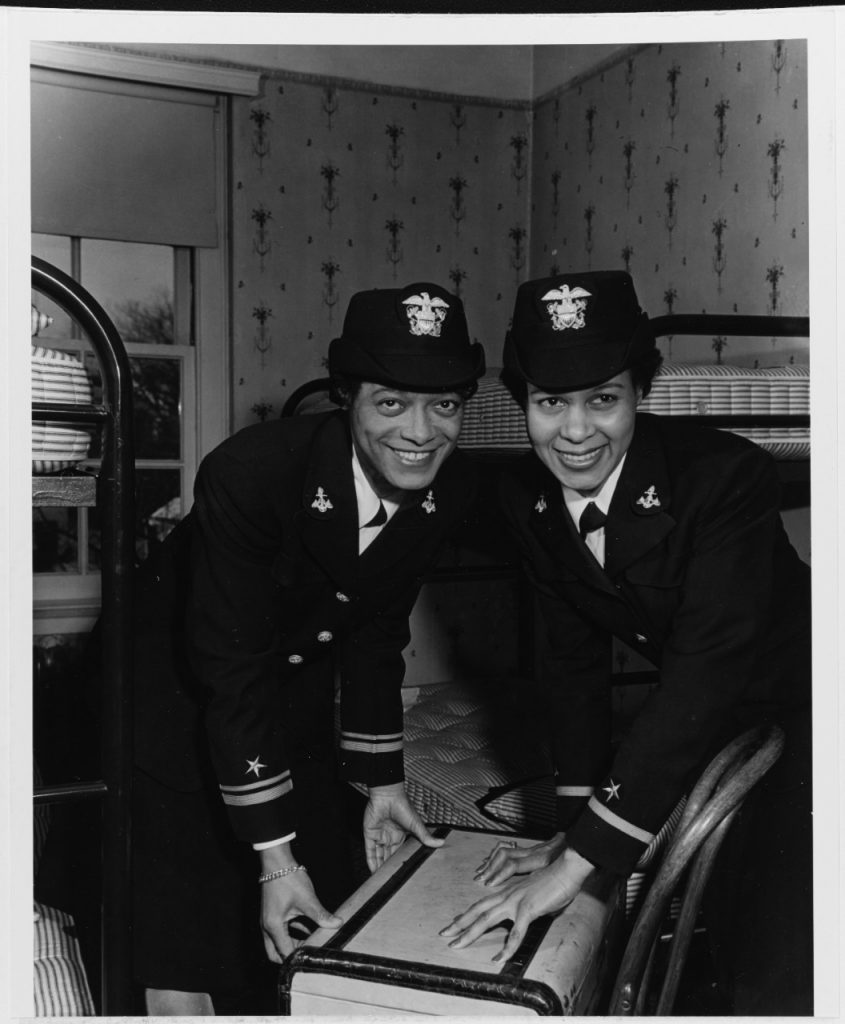

Strides were made within the Navy for black women as well. In October 1944, the WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service) opened recruitment for black women, and in March 1945, the Navy Nurse Corps was also opened to blacks.

Lt. (j.g.) Harriet Ida Pickens (left) and Ens. Frances Wills close a suitcase after graduating from the Naval Reserve Midshipmen’s School (WR) at Northampton, MA, 21 December 1944. They were the Navy’s first African-American WAVES officers and graduated with the Northampton school’s final class. (U.S. Navy Photograph)

Results

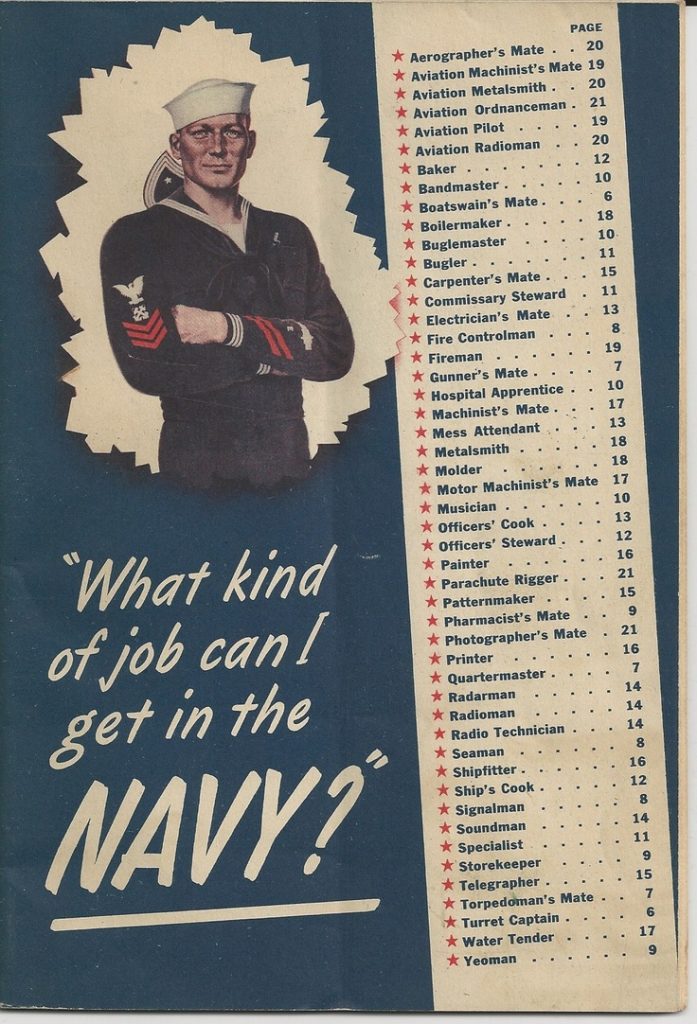

Progress in the Navy was slow but significant. By the end of the war, 5.3 percent of naval personnel were black, double the prewar percentage but still less than half the percentage of the population. Only 60 black officers served in the Navy, up from zero before the war. Seventy black women served as WAVES, and four black women served in the Navy Nurse Corps. Before the war, blacks were only allowed to serve as steward’s mates. By the end of the war, blacks held 67 different ratings, although 40 percent still served as steward’s mates.

Brochure about ratings in the US Navy, WWII

Full Integration

Work continued in the Navy after the war. On February 27, 1946, without fanfare, the Bureau of Naval Personnel issued Circular Letter 48-46 which prohibited all segregation in assignments, ratings, ranks, ships, facilities, and housing. Not until 1948 were the rest of the armed forces completely integrated. While the Navy had been the most segregated service before the war, it became the first integrated service. The events surrounding the Port Chicago Explosion played a significant role in these landmark changes.

Sources

MacGregor, Morris J. Jr. Integration of the Armed Forces 1940-1965. Washington DC: Center of Military History, United States Army, 1985. On U.S. Army Center of Military History website. Accessed 25 June 2019.

Allen, Robert L. The Port Chicago Mutiny. Berkeley CA: Heyday Books, 2006.

[…] I included these events in my third novel, Blue Skies Tomorrow. Last week I discussed the situation in the armed forces and at Port Chicago, today I’ll cover the explosion, and over the next few weeks we’ll look at the work stoppage, trial, and aftermath. […]

[…] Despite its significance, few people have heard about Port Chicago. I included these events in my third novel, Blue Skies Tomorrow, and over the next few weeks, I’ll discuss the situation in the armed forces and at Port Chicago, the explosion, work stoppage, trial, and aftermath. […]

One of the really odd features of segregation in the Navy is that it was actually introduced following the end of the age of sail.

Prior to ships becoming the steel vessels we think of today, which began in the late 19th Century, the Navy was’t segregated. That may be because the U.S. Navy, like all navies, recruited from the marine class that lived in every port city in the world. For that reason, it isn’t that uncommon to find sailors of any particular navy, for example, who were born in a country other than that which they were serving. An English born sailor, for example, won the Congressional Medal of Honor during the Civil War.

Once modern ships began to come in, sailors started principally being drawn from the interior of the country, in the case of the U.S. and they seem to have brought their prejudices into the service with them. The Navy therefore introduced segregation where it had not existed before.

I wrote a bit about this here: https://lexanteinternet.blogspot.com/2015/10/blacks-in-army-segregation-and.html

None of this is to suggest that life for blacks was pleasant or that they enjoyed full equality anywhere, which simply wouldn’t be true.

Fascinating! Your article was very interesting. I knew bits and pieces of the story, but not the full extent.

I think the part of it that strikes us as so odd, and in unjust, is that the Navy wasn’t segregated all the way to the end of the 19th Century and then brought in segregation.

It really reflects how industrial navies became. The Navy is steeped in tradition, but in reality modern sailors, those serving post 1890 or so, are closer in nature to industrial workers, for the most part, than traditional sailors. In the age of sail, navies took in men who were largely trained from their civilian occupations and knew how to operate sailing vessels. They didn’t worry that much about where they were from. When modern vessels came in, industrial arts dominated and the emphasis changed, along with the demographic base for all navies.

It’s also explains, in part, why the World War One German Navy and the Imperial Russian Navy were hotbeds of revolution. The industrial class necessary for an industrial navy were the radicalized classes in those countries.

Really nice website you have! Very interesting, and good luck with your books. Since you seem to be very interested in WWII, you might find my book Best Little Stories from World War II of some interest. In addition, my Proud to be a Marine touches on race relations—and changes—in the Marine Corps. Best wishes for now, CBK

Thank you for visiting, Brian! I’m so glad you’re writing about this fascinating era too! I’ll have to look for your book.