Port Chicago – The Work Stoppage

In the worst Home Front disaster of World War II, an explosion at the Naval Magazine in Port Chicago, California on July 17, 1944 killed 320 men, of whom 202 were black. The tragedy was followed by a work stoppage and a controversial mutiny trial. This sent ripples of change through the segregated armed forces.

These events were included in my novel Blue Skies Tomorrow.

This is the third in a five-part series on the Port Chicago Disaster:

Part 1: Introduction: Segregation in the armed forces and the situation at Port Chicago

Part 2: The explosion

Part 3: The work stoppage

Part 4: The mutiny trial

Part 5: The aftermath and desegregation of the US Navy

Survivors

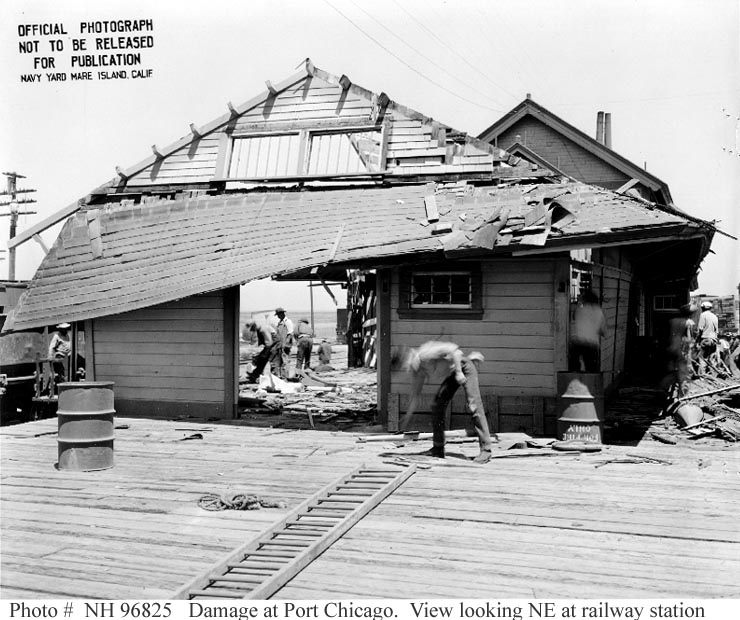

Damage to depot at US Naval Magazine, Port Chicago from 17 July 1944 explosion (US Naval History and Heritage Command)

After the July 17, 1944 explosion claimed 320 lives, most of the survivors were taken to Port Shoemaker in Oakland, CA. However, two hundred men remained to help in the grisly clean up. By the end of the month, reconstruction began, and the first berth on the new pier opened September 6, 1944. Survivors’ leaves were granted to the white, but not the black survivors.

Congress met to decide on payments to beneficiaries, usually $5000. However, when Senator John Rankin (D-Mississippi) heard most of the beneficiaries were black, he demanded lowering payments to $2000. Congress settled on the insulting amount of $3000, which applied to white beneficiaries as well.

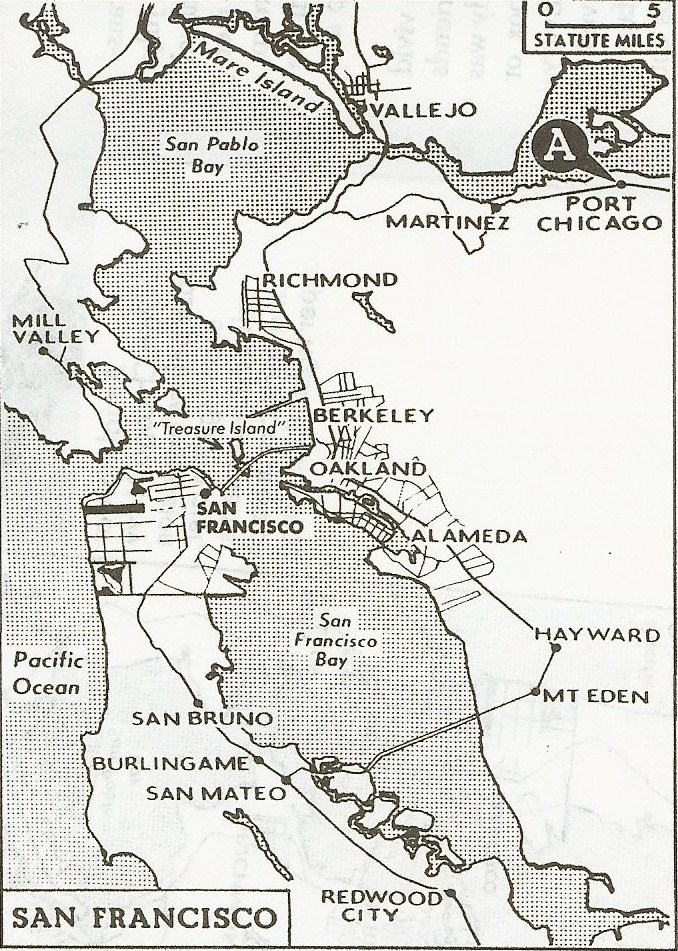

Since the war continued and the Navy’s need for munitions in the Pacific had not diminished, three of the surviving work divisions (all black) from Port Chicago were sent to the main depot across the river at the Mare Island Navy Yard in Vallejo.

Damage to barracks at US Naval Magazine, Port Chicago from 17 July 1944 explosion (US Naval History and Heritage Command)

Work Stoppage

The men remained jittery from the explosion that had killed so many of their friends. No new training was given, no new safeguards were instituted, and the men served under the same white officers from Port Chicago. Tensions rose as they realized they’d be asked to load ammunition again. They knew firsthand the hollowness of the promise that the ammunition couldn’t detonate.

On August 9, 1944, the men were marched from their barracks at Mare Island toward the dock to load ammunition again for the first time since the explosion. Suddenly, the men stopped marching. They said they were afraid to handle munitions and they’d obey any order except the order to load ammunition.

Upon further questioning from the officers, of the 328 men in the three divisions, 258 refused to work. These men were confined to a barge, since the brig wasn’t big enough. For three days, the men remained under guard on the crowded, poorly ventilated barge.

The Admiral’s Demand

On August 11, the 258 men were gathered on the baseball field. Admiral Carleton Wright, commander of the 12th Naval District, addressed the men. He informed them that refusing to work in time of war was mutinous behavior, and that mutiny carried the death penalty.

The men were asked again if they were willing to work, and 208 said they were willing, but the remaining 50 refused and were taken to the brig at Camp Shoemaker in Oakland, California. These 50 men included two who refused because they were mess cooks and had never handled munitions before—one had a nervous condition and the other was underweight. Another man refused to work due to a broken wrist in a cast.

Interrogations

All 258 of the men who initially refused to work were interrogated at Camp Shoemaker, under armed guard and without counsel. The transcripts of their testimonies were often wildly inaccurate, but they were given no choice but to sign the testimonies.

On September 2, President Roosevelt recommended that the 208 men who agreed to return to work receive light sentences. These 208 were given Summary Courts Martial and bad-conduct discharges, and were docked three months’ pay. The 50 men who refused to work were given General Courts Martial with the charge of mutiny.

Continue Reading: Part 4: The mutiny trial

Sources:

Allen, Robert L. The Port Chicago Mutiny. Berkeley CA: Heyday Books, 2006.

War Time History of U.S. Naval Magazine, Port Chicago, California. Washington DC: US Navy Bureau of Ordnance, 5 December 1945. On Naval History and Heritage Command website. Accessed 25 June 2019.

[…] at Port Chicago, today I’ll cover the explosion, and over the next few weeks we’ll look at the work stoppage, trial, and […]

[…] few weeks, I’ll discuss the situation in the armed forces and at Port Chicago, the explosion, work stoppage, trial, and […]

[…] blog posts discussed the situation in the armed forces and at Port Chicago, the explosion, the work stoppage, and the mutiny trial. Today’s post looks at the change that […]

[…] blog posts discussed the situation in the armed forces and at Port Chicago, the explosion, and the work stoppage. Today’s post covers the mutiny trial, and next week we’ll look at the […]